The epidemic of opiate overdoses in Massachusetts has abated somewhat this year, and the reduction may be due in part to the widespread availability of naloxone, commonly referred to as Narcan. Opioids can slow or even stop one's breathing when taken in excessive amounts or mixed with alcohol or other drugs. Naloxone is a lifesaving antidote. It blunts the effect of opioids and can restore normal breathing. In fact, carrying naloxone, which is widely available, allows anyone to be prepared to respond if they witness an overdose.

At one time naloxone was administered by trained health providers only, but the burgeoning epidemic called for another approach. Available in nasal form, naloxone is easily administered by people without medical training and obtainable without a prescription at most pharmacies across the state. The medication is sprayed into each nostril of the patient and has no abuse potential. It usually takes up to eight minutes to work. Generally one dose is sufficient, but in some cases, such as after a massive intake of opioids, another dose may be necessary.

Alexander Y. Walley, M.D.

Alexander Y. Walley, M.D., M.Sc., the associate director of Faster Paths to Treatment at the Grayken Center for Addiction at Boston Medical Center, spearheaded the efforts to make naloxone available to the general public. Walley is also the medical director of the Opioid Overdose Prevention Pilot Program with the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, and published a study on its impact.

The program was designed to examine the effect of overdose education and nasal naloxone distribution (OEND) on rates of death from opioid overdose. The participants — people who used opiates and their family or friends — were educated on the risk factors associated with overdose. They were also trained to prevent, recognize and respond to opiate overdoses by such measures as rescue breathing, calling 911 and administering naloxone.

Walley found that death rates from opioid overdose were reduced in communities that implemented the training. “The greater the implementation, the greater the impact. It appears that OEND is a promising, scalable and affordable tool to save lives from opioid overdose,” Walley told Boston Magazine.

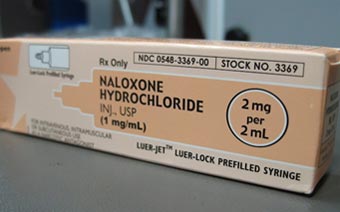

Nalaxone, commonly referred to as Narcan

Nalaxone, commonly referred to as NarcanThe study by Walley had a trickle-down effect. In 2014, the Commissioner of the Massachusetts DPH authorized “standing orders” for the dispensing of naloxone rescue kits in local pharmacies. Standing orders means that prescriptions from one’s physician are not necessary to receive naloxone. It is available not only to people at risk of experiencing an opiate overdose but also to people in a position to assist them should an overdose occur. Each naloxone rescue kit contains two pre-filled syringes of naloxone, two atomizers and information on overdose prevention and naloxone administration. By December 1st of this year, the Commonwealth mandates that all pharmacies honor standing orders for naloxone.

Between December 2007 and March 2014, the OEND programs implemented by the Massachusetts DPH trained over 22,500 potential bystanders and documented over 2,655 opioid overdose reversals. It is hoped that once standing orders are universal in the Commonwealth the number of reversals will increase substantially.

Traci Green, Ph.D., deputy director of the Injury Prevention Center at BMC, is one of the forces behind wide availability of naloxone, and helped make it obtainable at drugstores and community organizations across Massachusetts and Rhode Island. Increased availability, however, does not always translate to accessibility. Barriers may still exist. That is one focus of Green’s MOON (Maximizing Opioid Safety with Naloxone) Study. The purpose is to learn more about barriers that may inhibit access to naloxone in pharmacies. It will also examine the public’s perception of opioid safety and the role of the pharmacy in public health intervention.

BMC was the first hospital in the city to make naloxone available in the emergency department, according to a report published by Green for the Injury Prevention Center at BMC. The hospital took it a step further, and since January 2015, has been providing naloxone rescue kits to anyone who asks under a standing order from Dr. Walley.